Have you ever heard of the 10,000-hour rule?

It’s this idea that if you practice something for 10,000 hours, you’ll become an expert. It’s pretty well-known, and a lot of famous people like chess players, musicians, and athletes have achieved success after putting in those 10,000 hours. This is called quality practice training.

If you hear this story as a trainer, you must be delighted. You feel yourself nodding… Yes, Innate talent is overrated! Down with the fixed-mindset. Long live the growth mindset! You have to let people practice. Exactly the definition of your job as a trainer!

As trainers, we all want to help our participants practice and become experts, right? But here’s the thing – the 10,000-hour rule has some flaws. For one, the research it’s based on, is pretty specific, so it might not apply to all professions and skills. It also seems the number has been picked arbitrarily, it also could have been 8,000 hours or 12,000 hours. Besides that, it is very likely that they interviewed mostly people who succeeded to become experts after 10,000 hours of practice and not those who did not. Plus, the rule only focuses on the amount of practice, not the quality of it.

An example

And the last thing is something we like to zoom in on. Think of someone who is 60 years old and has been able to play the guitar since they were 25. During these years their practice has accumulated to over 10,000 hours but they only ever played some known songs at outings and campfires. They are far from being an expert. If this person had practiced 10,000 hours on specific elements of guitar play, on playing complex songs and chords, and done so while getting relevant feedback, we might have been able to call them an expert guitar player.

You see, the quality of your practice matters. It’s so important for us as trainers to design exercises that optimize learning outcomes. We need to figure out what exercises work best, how to build them into a series that helps people learn, and how to challenge our participants just outside of their comfort zones.

It is easy to be happy about your training program. You might always get good reviews. But be careful. Good reviews do not say anything about the impact your training has. Whether what your participants have learned is applied and whether they are on their way to become experts. In other words, it doesn’t always say anything about the QUALITY of practice you have offered.

How to include quality practice in your training design?

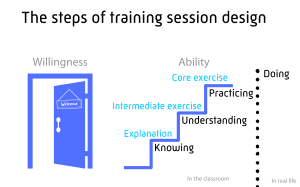

At iCRA we use the Learning Staircase from Karin de Galan to ensure the quality of practice. The idea is that you start designing your training from the reality of the participant and by designing the exercise that will reach your participants to become experts in handling that reality; the core exercise. In other words, you work backwards. Instead of starting with the theory, you start with the practice.

It looks like this:

Making Training Work!

If you are curious about this model and want to create really effective, engaging training sessions, we recommend checking out our course ‘Making Training Work’(link) on how to create an impactful training. During this training we practice what we preach, and you will experience firsthand what a quality practice looks like. And if you have already followed an iCRA course before, you’ll notice the continous improvements to our sessions based on feedback form participants ánd knowledge form other experts. After ‘Making Training Work‘, you’ll have created sessions that actually help people to apply the skills that they have learned in their reality in the most effective way.

Don’t just rely on your gut or your experience. Take a critical look at your training methods and consider how you can improve them to create sessions that make a real impact. You’ve got this!

This iCRA expert bite is written by Mariëtte Gross(link) and is inspired by a post from Arie Speksnijder, trainer of the year 2021 in the Netherlands.